Thermodynamic Cycle

| Free Energy Fundamentals |

|---|

|

|

Methods of Free Energy Simulations

|

| Free Energy How-to's |

|---|

|

In any free energy calculation, one must decide on what thermodynamic cycle they will define as well as the end states of their simulations. This is a very important step as it provides understanding of not only what the simulation is doing, but what you are calculating as well as clue you into what intrinsic errors you may encounter in your run.

Choosing End States

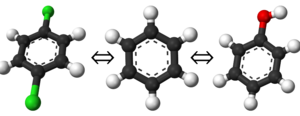

This is a straightforward enough concept. If you have two species or systems you wish to know the free energy difference of, you simply select the end states of the cycle as those two points. You are not limited to only two end states, but it becomes significantly more challenging to define a thermodynamic path connecting all the states as you increase in count. As a simple example of end states, consider the example shown on the left. Your end states could easily be any of the three molecules; benzene, phenol, or 1,4-dichlorobenzene; and your thermodynamic path would be one that linked two or all three together.

Although this may seem like a trivially easy task, it is an important one as the thermodynamic path you define will strongly depend on these. It is recommended for beginners to start with only pairs of free energy transformations instead of trying to estimate many end states at once; e.g. the sequence of benzene → 1,4-dichlorobenzene, benzene → phenol, then phenol → 1,4-dichlorobenzene (although this could be calculated from the first two).

It is very rare for researches to only need the end states to simulate in free energy calculations, so numerous intermediate states and an efficient thermodynamic path are needed. Because free energy is a state function, and because these are simulations, it's often better to select the most efficient or convenient path instead of the most physical path.

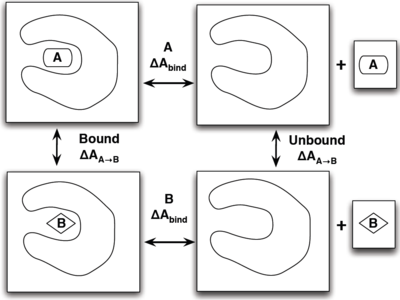

Constructing a Thermodynamic Path

The best way to show how efficient thermodynamic paths can make simulations quicker is with an illustrative example shown on the right. The situation is that we wish to find which ligand, A or B has a stronger binding affinity to our target protein. One rather physical way would be to simulate each ligand inside the pocket (left side), and have each ligand leave the pocket and move far enough away from the protein to be considered not interacting (right side). Constructing the intermediate states for this could include applying a bias to the ligand or making a large enough box for this to evolve on its own. There are several flaws with this though as it may take an incredibly long time for the system to evolve on its own, not to mention the large resources needed for an appropriate size box to simulate this.

A more efficient way is to simulate the transformation of A to B both in and out of the pocket in separate simulations and find the change in binding free energies that way by the equation

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta \Delta A_{\mathrm{bind}} = \Delta A_{\mathrm{bind}}^B - \Delta A_{\mathrm{bind}}^A = \Delta A_{A\rightarrow B}^{\mathrm{bound}} - \Delta A_{A\rightarrow B}^{\mathrm{unbound}} }[/math]

which does not require an excessively large box and can be done relatively simply by choosing the unphysical path of transforming the ligands. How you go about transforming molecules is covered in the constructing intermediate states article.

Because we are now taking a nonphysical path, we must be even more judicious with our verifications. For instance, if you are running a constant volume and temperature simulation, your end states should have the same box volume and temperatures, even if you alchemically changed molecules. Despite the fact that we cannot replicate the thermodynamic path experimentally, there are still restrictions and rules we must abide by to ensure our results are valid.

One of the easiest errors to make when beginning free energy simulations is to turn off all molecular interactions if you are removing an atom or molecule and assume this result is the free energy difference. Remember that our free energy difference is the system with the molecule present, and the system with the molecule existing on its own, so intramolecular interactions should have remained on. If you turn off all interactions, then either a second simulation or a correction will be needed to give you the correct results.