Free Energy Fundamentals

| Free Energy Fundamentals |

|---|

|

|

Methods of Free Energy Simulations

|

| Free Energy How-to's |

|---|

|

To understand the advantages and disadvantages of different free energy methods, it is important to begin with a review of the underlying principles. This page is dedicated to the most fundamental concepts of free energy calculations and is designed to give an in-depth view of the approaches, starting from the basics. This page also contains some of the common nomenclature and symbols that are seen throughout the rest of the free energy fundamentals pages and in the literature as a whole.

This page is not meant to be an end-all repository of the background mathematics and principals required for free energy calculations, but it will serve as a good start point and hopefully a quick reference.

Why the name "Alchemical"?

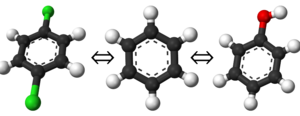

One of the first questions, and often most confusing points, about a number of free energy calculations is why we refer to them as "alchemical" changes in a large number of computational methods. When people first hear the word "alchemy," they usually think of the medieval alchemists who were trying to turn lead into gold, or other such transformations. How computational free energy adopted the name takes a bit of understanding of simulation limitations and the properties of what we are calculating.

Considering that the natural evolution of some of the processes we try to model are well beyond reasonable simulation time scales, we must come up with very efficient ways to compute the free energy differences. Because free energy is a state variable (path independent), we can design simulations that provide a convenient pathway to computing free energy. Furthermore, since we are doing simulations, we are not limited by experimentally observable conditions so long as we are meticulous with our calculations.

With these observations in mind, it was found that we can simulate modifications to atoms which can change their properties to reflect non-physical or entirely different species. This is roughly the same definition of alchemy from old in that we are changing the properties of the atoms to be something else, although we do it in a mathematically sound and rigorous manner; hence, the term "alchemical" was coined as many free energy calculations are "like alchemy" in their pathways and methods.

There are of course many factors and checks that must be done to ensure accuracy and robustness of the calculations, many of which will be shown in the rest of the free energy fundamentals pages.

Assumptions for the Fundamentals

The assumptions listed here are carried out through the rest of the fundamentals sections. Free energy calculations can usually be set up without these assumptions, but we'll make these assumptions to simplify the explanations.

- A standard molecular mechanics model will be assumed; this includes:

- Harmonic bond angle terms

- Periodic dihedral terms

- Non-bonded terms made up of point charges and Lennard-Jones repulsion/dispersion terms

- constant temperature is maintained: (discussed below)

- Masses do not alchemically change. If one wishes to do this, substitute all potential energies, [math]\displaystyle{ U }[/math], with the more general Hamiltonian, [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{H} }[/math].

- QM/MM will not be considered for fundamental; there are number of other more complicated factors to consider that are beyond the scope of this discussion.[1]

Free Energy Difference Equation

Most free energy calculations and methods started from a single core equation derived from statistical mechanics. The free energy difference between two states is directly related to the ratio of probabilities of those states through the partition functions. This free energy difference for an NVT ensemble is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \displaystyle \Delta A_{ij} = -k_B T \ln \frac{Q_j}{Q_i} = -k_B T \ln \frac{\int_{\Gamma_j} e^{-\frac{U_j(\vec{q})}{k_B T}} d\vec{q}}{\int_{\Gamma_i} e^{-\frac{U_i(\vec{q})}{k_B T}}d\vec{q}} }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta A_{ij} }[/math] is the Helmholtz free energy difference between state [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math] and state [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ k_B }[/math] the Boltzmann constant, [math]\displaystyle{ Q }[/math] the canonical partition function, [math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math] is the temperature, [math]\displaystyle{ U_i }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ U_j }[/math] are the potential energies as a function of the coordinates and momenta [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{q} }[/math] for two states, and [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma_i }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma_j }[/math] are the phase space volumes of [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{q} }[/math] over which we sample, or the total set of all allowed positions and momenta of the system.

From this equation, all free energy calculations are derived.

Facts from the Free Energy Difference Definition

There are a number of key notes we can learn from the definition of free energy differences. Each of these can be important in interpreting simulation results.

- Only free energy differences are ever calculated. There is never a calculation where absolute free energies are needed (and rarely can they be calculated at all) as all of the biological or thermodynamical quantities of interest are based on a free energy difference. As such, there must always be a minimum of two defined thermodynamic states.

- Even absolute free energies of binding are still free energy differences between two states: the ligand restricted to the binding site, and the ligand free to explore all other configurations.

- Free energy differences between states at different temperatures are usually not what you want to be calculating for problems of interest. If it did, you would get [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta A_{ij} = -k_B T_j \ln Q_j + k_B T_i \ln Q_i }[/math], which is no longer a ratio calculation and not needed for biological systems of interest. Temperature dependence on free energy is more likely to be "what is [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta A_{ij} }[/math] change at two different temperatures?"

- There are two different phase space volumes. [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma_i }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma_j }[/math] are often the same, but they are not required to be. The methods presented here almost always assumes that the two phase spaces overlap. However, when the spaces do not overlap, these methods break down and it is difficult to identify this problem without in depth knowledge of your system. Consider the example of a hard sphere solute with radius [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math] at state [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] and a Lennard Jones repulsion/dispersion potential, with the same [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math] at state [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math]. Since [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma _i }[/math] will not have molecules at a distance less than [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math], but [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma_j }[/math] will, the two phase spaces are not the same and these methods will either break down or return very error-prone results.

- The degree to which the phase spaces are shared is called the "phase space overlap". Efficient free energy calculations require significant phase space overlap. There are a number of strategies to address lack of overlap between target spaces, but determining the best way for any given situation is still a research question.

- It should also be noted that "near zero probability" and "always zero probability" are two distinct things when considering phase space. So long as there is a chance for an observation to be made, no matter how small, it is considered part of the phase space.

References

- ↑ Woods, C. J., Manby, F. R., and Mulholland, A. J. (2008) An efficient method for the calculation of quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics free energies. J. Chem. Phys. 128, 014109. - Find at Cite-U-Like